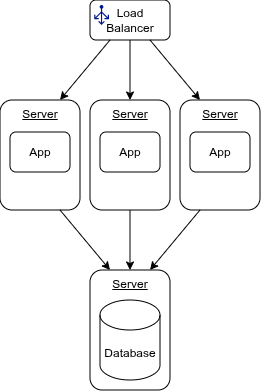

Traditionally, a monolith application is deployed to one or more servers, commonly referred to as “Application Servers”. These application servers could be bare metal or virtual.

There could be one or many of them in cluster behind a load balancer. Having more than one is typically for redundancy– one server can fail and the other(s) can still handle requests–and for load–a single server may not be able to handle peak request volume. So our deployment diagram would look something like figure 1.

Figure 1

Let’s compare and contrast how we would traditionally deploy this type of application with how we could do it using Docker.

Assumptions and Application Prerequisites:

Assumptions

- The application is a monolith written in AspNet Core and is framework dependent.

- The application is deployed to three servers behind a load balancer. Whether these are bare metal or virtual is irrelevant.

- Only this application is deployed to these servers.

- The application talks to a database server.

- The application server is running Ubuntu Server (but could just as easily be Windows).

- We are deploying to servers in a private data center, not a public cloud.

- All servers and devices in the datacenter are assigned a static IP address.

Application Prerequisites

- .Net 10.0 AspNet Core Runtime

- i8n packages os packages for globalization

- timezone database

Traditional Provisioning and Deployment

Traditionally, the application server is built with any required prerequisites. In a virtualized environment, teams often keep a base image that has the necessary requirements so they can quickly create new application servers as needed. Provisioning a bare metal server is an automated fashion could be handled with something like MaaS from Canonical.

Dotnet applications simply need to be copied to the server. There is no install. However, we often want to create a systemd service (or a Windows Service on Windows Server) so we can auto-start the application when the server boots.

Deployment could be manual. If this is the only application, it is only on a couple servers, and is deployed at most once a month or so, this may be sufficient. Though, anything manual, no matter now simple, leaves room for human error, so, often, this process is automated. There are lots of tools for doing this. It could be as simple as FTP and a bash script or something a bit more sophisticated like Ansible, Chef, Puppet, or Canonical Juju. However you choose to automate the process, there is some scripts and artifacts to be maintained. Regardless of how, someone or something needs to run scripts on the servers remotely and must know which servers to run them on.

This works perfectly fine and has for decades. However, some issues can crop up:

- Dependencies, including the OS itself on any base images can get easily become out of date and vulnerable.

- Automated updates on the running production servers can cause apps to break or exhibit odd and undesirable behavior.

- Environments, especially local dev workstations, can be out of sync with what production is actually running. We’re all familiar with the phrase “Works on my machine.”

There are operational considerations as well:

- What happens when the app crashes? How does it restart?

- How do we monitor the health of the application?

Using Docker

Let’s see how we can leverage containers and Docker to deploy this same application. Just as with the traditional setup, we need a set of application servers. This time though, the prerequisite for the server is docker-ce and any dependencies it needs. Just as we did in the traditional setup, this can be manual or automated, use a base VM image or MaaS. The application prerequisites till be part of the container image.

Additionally, we will enable Swarm Mode on each node. When running in a swarm, we get some management goodies:

- Any manager node can be used to deploy the application

- Docker will ensure the number of replicas is always maintained.

If there are only a few servers like in our example of three application servers, each server can be a manaqer node. This greatly simplifies deployment.

For our app and its requirements, we build a container image as part of our application’s build and packaging process. We will also create a deployment manifest for it. This is a simple yaml file that tells docker how to deploy and run the container on the swarm.

Deploying the application could be done manually. It is a very simple:

docker stack deploy --compose-file compose.yaml stackdemo

services:

app:

image: stackdemo

ports:

- "8000:8000"

We can get fancy with the docker compose files and have files for setting up a local dev environment with all services and for production where we just need the app.

Advantages:

- Every environment, including local development, is identical. No more surprises because production is using a slightly different version of the OS and dependencies.

- For simple clusters, we only need to know the cluster’s dns or address. Any swarm manager can accept the deploy request and swarm will deploy the app to every node.

- Deployment, monitoring, and management are arguably simpler.

Putting It All Together

I’m keeping it very simple but production quality. Automating these steps is out of scope for this article but simple enough to implement in any provisioning solution.

Provision the Application Servers

Install docker:

sudo apt install docker-ce

Create the swarm on node 1:

docker swarm init --advertise-addr <MANAGER-IP>

The command will initialize a new swarm and generate a token. The command and token it outputs is for joining workers. We want all three of our nodes to be managers. This provides redundancy and allows any node to answer a swarm API request. So, we need to get the manager token:

docker swarm join-token -q manager

Join the other two nodes to the swarm. On server 2 and 3 run:

docker swarm join --token <manager-token-from-the-previous-step> <MANAGER-IP>:2377

That’s it. Our cluster is now a docker swarm and is ready to have applications deployed to it.

We need a docker file that defines our application container. Using the chiseled-extra base image includes all the dependencies our app needs.

dockerfile

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/aspnet:10.0-noble-chiseled-extra

WORKDIR /home/app

COPY dist .

ENTRYPOINT ["dotnet", "myapp.dll"]

We need a script to build the app, build the container image, and deliver the image to our container registry.

The script is very minimal but is sufficient for most teams and environments. It even fails the build if any of our

nuget packages have vulnerabilities. We can easily augment the script to include things like a code scan.

The || exit 1 says if the command fails for any reason, exit the script. This ensures we don’t execute the next step

if the current step fails.

build.sh

#!/bin/bash

if [ -z "$1" ]; then

echo "Supply a version";

echo "Example: ./build.sh 1.0.0"

exit 1;

fi

version= $1

# Build and Test

dotnet restore || exit 1

dotnet list package --vulnerable --include-transitive || exit 1

dotnet build -p Version=$version --no-restore || exit 1

dotnet test --no-build || exit 1

dotnet publish --no-build -o dist || exit 1

# Package and Deliver

docker build -t myapp:latest -t myapp:$version || exit 1

docker image push -a || exit 1

echo "Completed successfully!"

The difference between this build script and the traditional one is the docker commands. Instead of:

docker build -t myapp:latest -t myapp:$version || exit 1

docker image push -a || exit 1

A traditional script not using docker would have something like:

tar -cvfz myapp-$version.tar.gz dist/

sftp -b - your_username@artifacts.acme.com <<'EOF'

put - /remote/path/myapp-$version.tar.gz

EOF

… to zip up the file and ftp it to a server for Ops to grab. So really no significant difference between a traditional script and one using docker. Both have steps to package up the app and deliver it to some location for the Ops Team to grab.

We also need a myapp-stack.yml file to describe our production deployment:

myapp-stack.yml

services:

app:

image: myapp:${MYAPP_VERSION:-latest}

ports:

- "8443:8443"

deploy:

mode: global # one replica per node

restart_policy:

condition: any # restart if the container fails and aborts for any reason

To deploy into an environment, Ops needs only the yaml file and to run:

MYAPP_VERSION=1.0.0 && docker stack deploy -c myapp-stack.yml myapp

This command could be run manually or as part of an automated deployment pipeline.

That’s all there is to it. A single deploy command and docker will ensure an instance of our application is running on each node in the cluster.

The traditional approach would be on each server to copy the tar ball to the server using sftp and expand it, with the added step of running a script to create a systemd service to start the application on server startup.

Conclusion

Without any additional complexity over a traditional deployment, we can leverage docker to streamline our monolith deployments. You could argue this setup is less complex than copying a zip file to each machine.

| Step | Traditional | Container |

|---|---|---|

| Package | Zip/Archive file. | Container Image |

| Delivery | Shared location e.g. FTP server. | Container Registry |

| Deployment | Script run on each machine manually or by automation tool. | Stack manifest yaml and run docker stack deploy once against the cluster |

| Infra prerequisites | Bare metal or VM with any infra automation installed e.g. Chef Agent. | Bare Metal or VM with docker in stalled and swarm initialized. |

| App prerequisites | Managed by the infra/ops team. Environments could be out of sync. | Managed in the container image at build time. All runtime environments always identical. |

One drawback to swarm mode is the IP addresses must be static and known in order to create and join a swarm.

We used a .Net application for the example, but the same approach can be used for Java, PHP, Python, Ruby, or any other type of app.

If you need more features and capabilities than are offered by a docker swarm, Kubernetes works just as well for this. K3s would be a logical step up, giving you much of the same the goodies of k8s with the simplicity of swarm–you can create a small three node cluster like we did above without needed dedicated manager nodes like you (should) do with K8s.

For reference, Shopify deploys their monolith using containers and Kubernetes.