Customer-First. Team-Focused.

I like to take a customer-first approach to architecture and software design. A system architecture should always deliver value to the customer. Either directly–features, user experience–or indirectly by enabling teams to deliver value.

If a team is going to be able to deliver value, the system needs to be easy to reason over, easy to maintain, easy and safe to extend, and easy to operate.

Every architecture or design decision should answer:

How does this deliver value to my customer?

How does this deliver value to my team?

Competing Styles. The Swinging Pendulum.

It seems the big debate lately is monolith vs microservices. Academically, each at the opposite end of the spectrum: the massive, single deployable unit monolith on one end and the highly decomposed highly distributed microservices on the other. Each come with their pros and cons and serve teams better depending on team size, skill level, and goals.

Notice I didn’t include the customer in that debate. The reality is, the customer doesn’t care. All the customer cares about is the user experience and the value the system is providing them. Your architecture can use every hot buzzword in the industry, if it is slow, unstable/unreliable, and doesn’t produce anything of value, the customer isn’t going to buy/use it.

Something a bit more Pragmatic

Is there something a bit more middle-of-the-road? Yes. We can take a pragmatic view of our architecture and design. For very small teams, that could simply be sticking with a well architected, modular monolith. For teams that can gain improvements from decomposed, independently deployable services, let’s take a quick look at a couple ways we can derive service boundaries that aren’t the text-book DDD Bounded Context but still give us some of those key benefits SOA can provide.

Business Capability

Define module/component/service boundaries around business capabilities–Feature Driven Development (FDD). I’m not alone in this belief. Martin Fowler and James Lewis concur. Even if you are using a monolithic deployment model (yes, monolith vs microservice is a deployment concern), organizing your components (and code) by feature/business capability makes it trivial to break that feature out into it’s own deployable should the need arise.

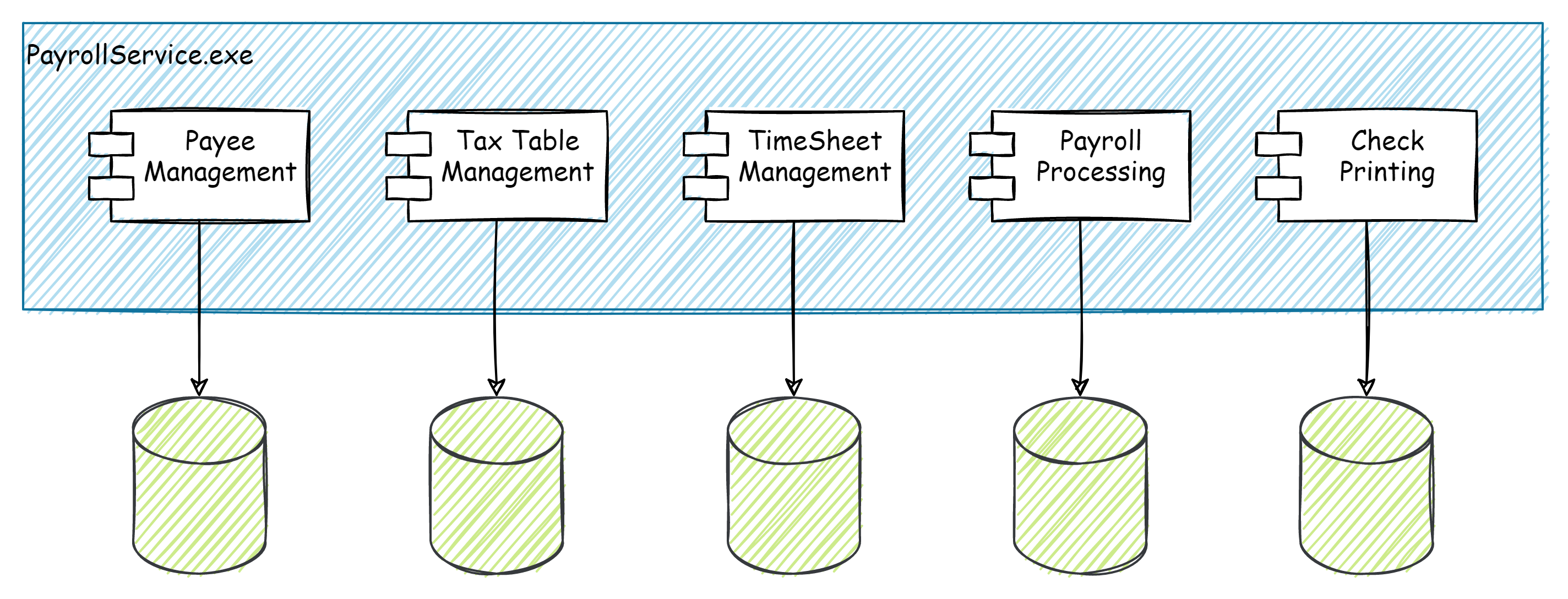

For example, let’s consider a module that performs payroll processing functions for an HR/Accounting application. We would start by defining the business capability here as Process Payroll. We can then imagine a (micro)service that encapsulates all the payroll bits of the system.

In a pure DDD approach, we would define our service boundaries around each aggregate root. You could end up with a microservice for the payroll run, one for managing employees, one for managing tax tables, another for timesheets, maybe yet another for printing checks.

You could argue that these are each their own business capability or feature of a payroll system, and should be broken out even under this paradigm. Why not keep it simple and start with a single Payroll Service. It is still doing one thing–Payroll–and doing it well. It keeps the functionality of payroll separate from other functions of the system such as invoicing or book keeping, which means they can evolve independently. Our payroll service also passes the autonomy litmus test–it can be deployed independently of other services. Those individual sub-features that we identified as possible candidates for their own microservices, we can (and should) organize in our code by sub-feature using FDD. This organization makes it easy to reason over–identify what code is doing what–and easier to refactor out into a separate service later if needed.

So to review:

- Autonomy

- Single purpose (depending on how course or how granular you define single purpose)

- Tested and deployed independently

- Domain logic/business rules for payroll all in one place

- Sub-features organized in their own sub-components.

Asynchronous vs Synchronous Work

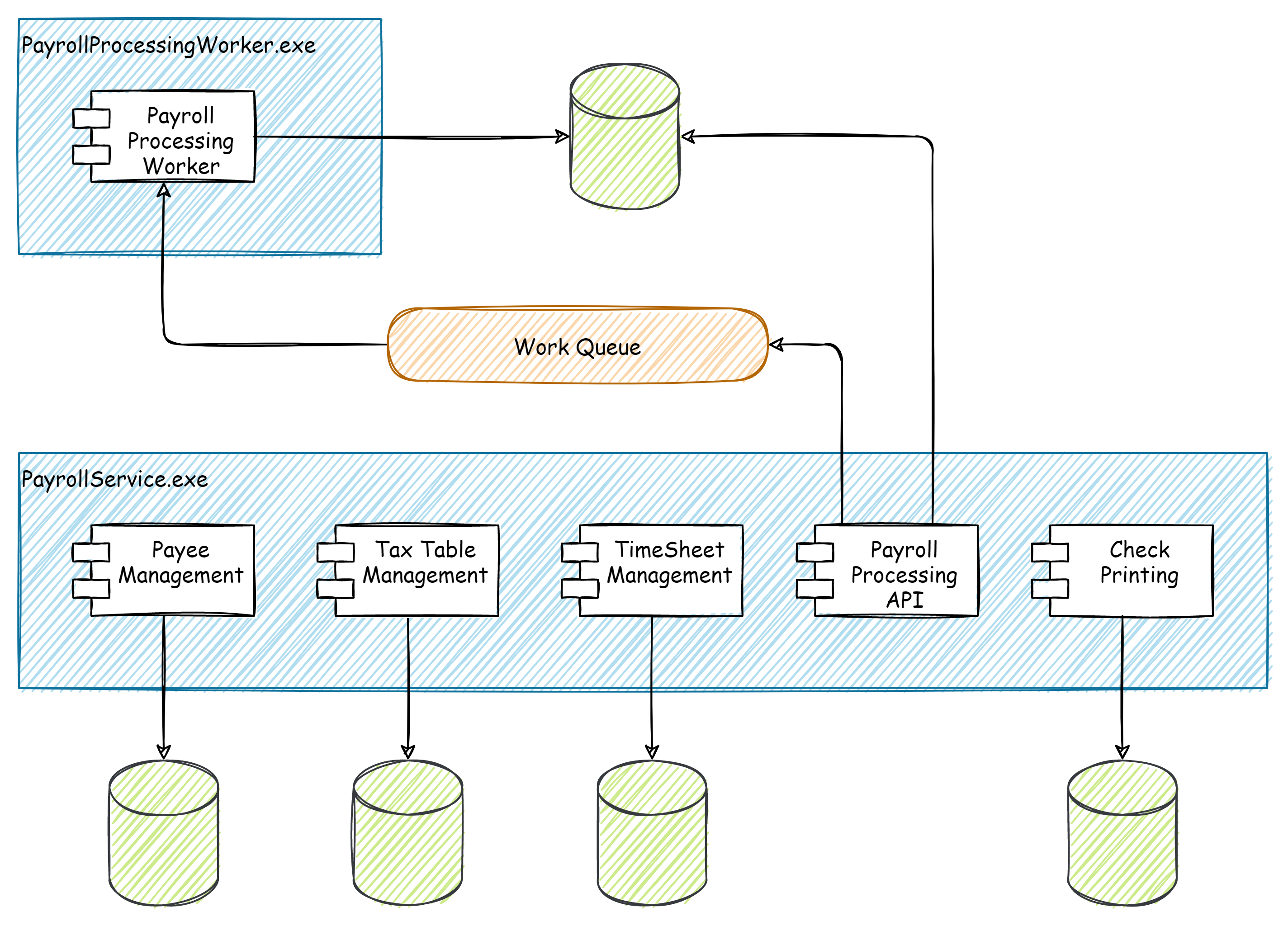

In the payroll example above, during our testing, we find that the actual processing of payroll takes several minutes to complete and API requests timeout. We have identified a long running process that isn’t well suited for a simple request/response API.

Since our code is SOLID and well organized around FDD with clearly defined feature components, we can easily break out the processing component into it’s own deployable service. Using our trusty Worker Queue Pattern, our Payroll API can now just accept the request from the user, submit it to a queue for processing, and return back to the user immediately.

Our Payroll Module is now two decoupled services. Because they communicate asynchronously on a queue and have no knowledge of the other’s existence, they can retain their deployment and evolutionary autonomy.

We can now scale the PayrollWorker, as needed, independent of the rest of the payroll system. We kept life simple and only introduced complexity where it benefitted the customer. The other operations and capabilities within the payroll service are primarily CRUD related–data maintenance–so there is little pragmatic reason break these out and introduce unnecessary complexity into our system.

Summary

Start course. Draw deployment boundaries around higher level business abstractions that make sense and the team can manage. Organize the code within those services by sub-feature to 1) make it easier to reason over, 2) make it trivial to break that sub-feature out later.

Defining boundaries around business capabilities rather than data transactions (bounded context) allows us to be as course or as fine-grained as needed and still follow the same approach. Since the Customer, Sales, and Product Manager are always speaking in terms of feature, it reduces the cognitive load for everyone involved in the SDLC–“FeatureX code is in the FeatureX service/module/package.”, “I’m testing FeatureX so I need to deploy FeatureX service into my QA environment.”